We're alive because the cosmos exists.

We exist today in 2017 because the universe has existed for 13.8 billion years. From the big bang, to the early formation of galaxies, to quasars, to supermassive stars, to stars like our Sun. All of that needed to happen just so that we could get to now.

This isn't an easy perspective to take in, but here we go.

Our Sun is about 4.6 billion years old; one third the age of the cosmos. Before Earth even existed, the cosmos was already 9 billion years old. These numbers are meaningless. Our brains aren't wired to comprehend them.

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field. A lot of really old galaxies, a really long way away. Image: NASA/ESA.

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field. A lot of really old galaxies, a really long way away. Image: NASA/ESA.

There are 7 billion people living on Earth, give or take. If you wanted to say hello to every single person, one at a time, it would take you 111 years to get to everyone (assuming you can say hello twice per second, without ever stopping). Divide this workload into a 40-hour work-week, and it would take you 466 years to accomplish the task.

At that rate, even just saying hello to everyone in North America would take four decades. It would take me two years of 40-hour work weeks just to say hello to everyone in Canada—and that doesn't even take holidays into account.

The numbers are mind-boggling.

Here's another one for you: 100 billion (100,000,000,000). That's the low estimate of how many stars exist in our galaxy. And another one: two trillion (2,000,000,000,000). That's a big estimate of how many galaxies may exist in the observable universe (and there are more out there that we'll never be able to observe).

As human beings, we're forgiven for not being able to wrap our heads around these numbers. We're finite flesh-bags straddled on either side by eternity. And our fragile existence is completely dependent upon a giant perpetual explosion, 1.4 million kilometers in diameter, 150 million kilometers away in space.

We call it the Sun, as if it were something we could control—or something we could reach out and touch.

As the Earth rotates and we lose sight of the Sun on the horizon, we call it as a Sunset. And when we come back in view of the Sun, it's a Sunrise. As if this massive nuclear explosion in outer space is somehow moving across our sky. It's not moving. We are. And while we drink our coffee or watch our Netflix, we don't even think about it.

You'd think the Sun could just kill us all at any moment. Image: NASA/SDO/AIA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

You'd think the Sun could just kill us all at any moment. Image: NASA/SDO/AIA/Goddard Space Flight Center.

We're out of touch with the way the cosmos really is.

What we call "The Sun" is a semi-benevolent celestial object that's been spewing photons out into space for billions of years. On our relatively small rock, those photons are captured by plants and algae and transformed by photosynthesis into an energy source. A byproduct of this process is Oxygen, which us humans need in order to continue breathing and living.

Those photons originate from gravity. The Sun is so large and its gravity so strong that elements in its core are crushed until they fuse with one another, forming heavier elements. This process releases a lot of energy, some of which reaches the surface of Earth as light, and then some of that is re-purposed by biological life.

We owe our entire existence to the fact that gravity causes really big things to crush really tiny things.

This process started 13.8 billion years ago, with a Big Bang. We don't know what happened before this bang, or what caused it in the first place. All we do know is that protons and electrons came together, and Hydrogen was formed. Then Hydrogen began clumping together because of gravity, and this sparked the formation of gigantic stars.

At the cores of these gigantic stars, the gravitational crush was so intense that really heavy elements could be created through fusion (far heavier than what our Sun can produce). Once all of their initial Hydrogen fuel had been used up, a lot of these stars exploded, spewing heavy elements (like Helium and Carbon) throughout the cosmos.

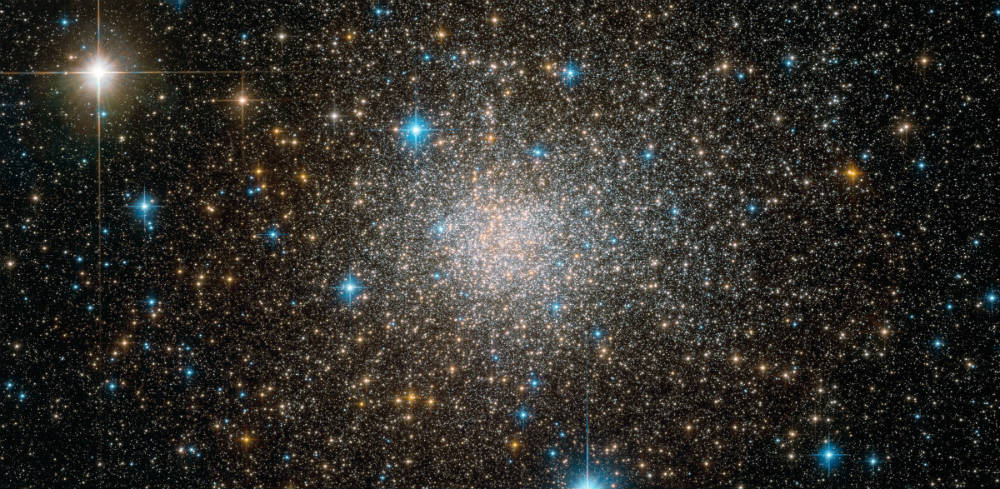

Artist's impression of what an exploding star looks like. Image: ESO.

Artist's impression of what an exploding star looks like. Image: ESO.

Over time, this process continued. Material clumped together as the universe continued to expand. Galaxies, including our own Milky Way, eventually formed and stabilized into the types of galaxies we see today.

By the time our Solar System formed, there were enough heavy elements strewn about the cosmos that planets like Earth could form around our Sun. And now, here we are.

The cosmos and the properties that describe it are what gave rise to us, to human beings. We exist at this present point in time. We have some idea of how we got here, but we have no idea what the future of our species will look like.

One thing we do know with relative certainty is that we're all going to die. Not just human life, but all life on Earth. In 4 billion years, our Sun will have burned through its Hydrogen fuel and begun a process of rapid expansion. The Earth will be scorched into oblivion.

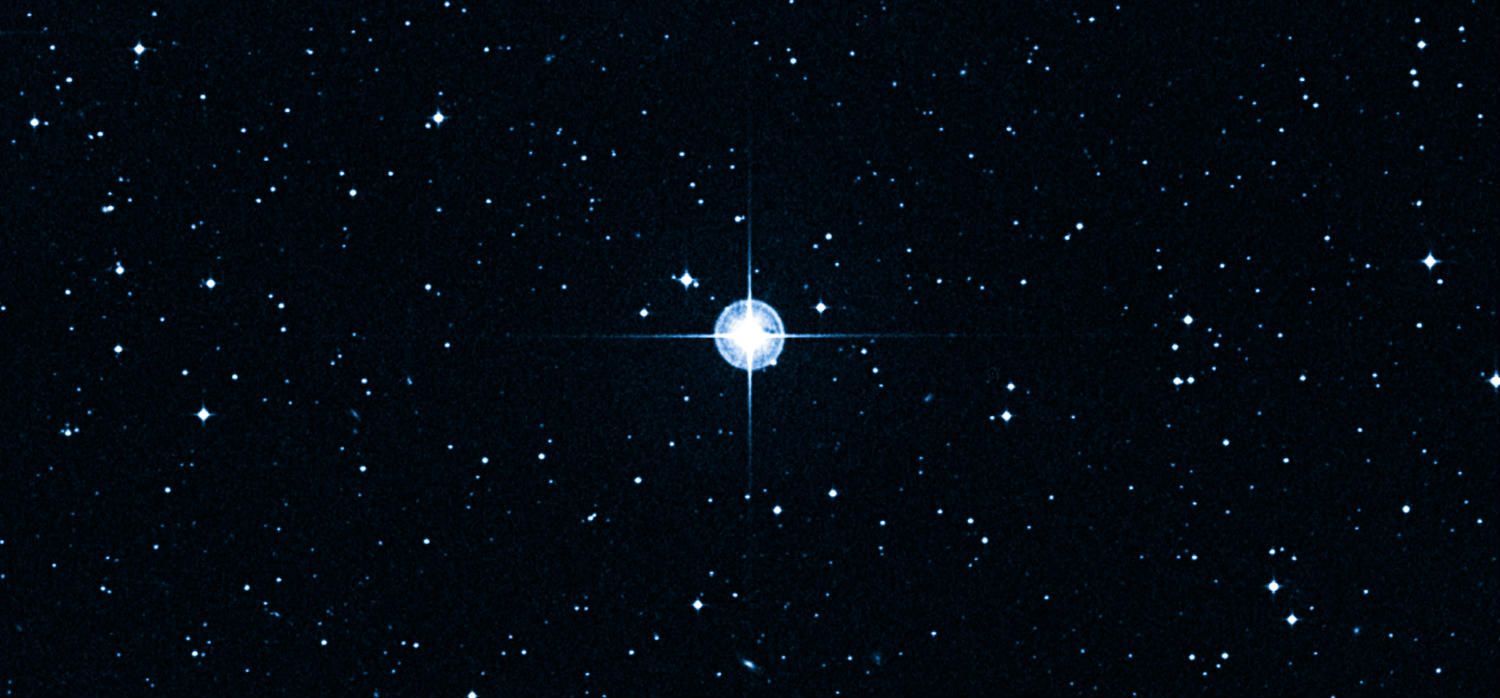

The cosmos is nothing if not terrifyingly destructive. Image: Jon Morse (University of Colorado), and NASA.

The cosmos is nothing if not terrifyingly destructive. Image: Jon Morse (University of Colorado), and NASA.

We'll eventually have to become interplanetary nomads—if we survive that long at all. Some unforeseen cosmic catastrophes may yet come our way, with the potential to end human civilization in a flash. And yet, even if we do manage to navigate all of these dangers, our fate is still sealed.

In the deep, deep future of the cosmos, entropy will tear everything apart. It starts with galaxies moving away from each other faster than the speed of light. Some of the most distant objects in the universe are probably already doing this, and that's why we'll never see them: their light will never reach us, because we're moving away from them faster than light can travel.

In a really, really long time, we won't be able to see any other galaxies. And after that, even nearby stars will begin moving away from us faster than the speed of light. This is a natural function of the expansion of the universe—like inflating an infinitely large balloon, the circumference continues to expand, forever.

A long time after this, even black holes will evaporate and disperse into the cosmos. Every atom in the universe will be flung apart from every other atom in the universe. Eventually, even atoms themselves will be torn apart from entropy.

This physical process is described in the Second Law of Thermodynamics. In simple terms, this mechanism states that matter always attempts to achieve equilibrium (that is, equal distribution) across any given system (ie. the universe). Therefore, the destiny of the cosmos is for all matter to spread out evenly throughout the universe.

All of the matter in the universe will spread outwards forever. That's entropy. Image: ESA/Hubble.

All of the matter in the universe will spread outwards forever. That's entropy. Image: ESA/Hubble.

The problem with this is that there appears to be a finite amount of matter but an infinite amount of space. This means that all matter in the cosmos will attempt to fill an infinite container which, by definition, can never be filled.

Everything that exists now will eventually be destroyed. There are no exceptions. In untold billions or trillions of years, nothing will survive. Not even a fragment of our past existence will persist, and everything will be wiped clean in the natural evolution of the cosmos.

This is our cosmic perspective. We're born because the cosmos has been steadily evolving for 13.8 billion years. Then, we partake in the universe with our minds—we define ourselves and what we are. We exist as the smallest, tiniest fraction of the cosmos, and because of this we're never able to fully comprehend its existence.

And, eventually, we'll all die. It doesn't matter if we're remembered, because we'll also be forgotten. Forgotten by the living and the dead, by the stars and all the planets, by all the things that ever were. Everything that exists will be erased. Our annihilation will be total.

But that's the future, not the present. For us, as finite beings, the future is irrelevant. Our lives take place here and now, and all we can do is live here and now.

We're only a fraction of the totality of the cosmos. And here we are, front row, witnessing the whole of the cosmos slide towards eternity.